- Free Consultation: (813) 222-2220 Tap Here to Call Us

Florida Automobile Exception Search and Seizure Lawyer Explains Illegal Vehicle & Cell Phone Searches

Florida Automobile Exception Search and Seizure Lawyer Explains Cabrera Leon and Illegal Vehicle & Cell Phone Searches

Florida Automobile Exception Search and Seizure Lawyer Explains Cabrera Leon and Illegal Vehicle & Cell Phone Searches

The Automobile Exception – If you’ve been told that police can search your car without a warrant, that statement is only partially true—and dangerously oversimplified. As a Florida Bar Board-Certified Criminal Trial Lawyer, I regularly litigate vehicle searches, cellphone seizures, and warrant challenges. One of the most important Florida trial-court decisions exposing how far law enforcement sometimes overreaches is State v. Cabrera Leon, 33 Fla. L. Weekly Supp. 370a.

This case is a masterclass in what probable cause is not, why uncorroborated tips are not enough, and how the automobile exception does not excuse constitutional shortcuts. More importantly, it shows how illegally seized vehicles and cellphones poison everything that comes afterward—including search warrants.

If your car was seized, your phone searched, or evidence was collected without a warrant, this is the kind of case I use to suppress evidence and dismantle prosecutions.

👉 If you are facing charges after a vehicle or cellphone search, contact me immediately:

https://www.centrallaw.com/contact-us/

Why the Cabrera Leon Case Matters

The Cabrera Leon opinion is unusually candid. The court didn’t merely suppress evidence—it condemned the investigative mindset that allowed officers to act on rumor, speculation, and hope rather than constitutionally required facts.

Three Critical Questions

At its core, the case answers three critical questions:

- Can police seize a vehicle based on an unverified tip?

- Can officers rely on the automobile exception without probable cause?

- Can an illegal vehicle search be “fixed” later with a warrant?

The answer to all three, emphatically, is no.

Key Facts of the Case (Simplified)

| Event | What Police Did | Legal Problem |

|---|---|---|

| Vehicle Stop | Stopped defendant late at night | Based on uncorroborated tip |

| Vehicle Seizure | Towed and impounded car | No probable cause |

| Cell Phone Seizure | Took multiple phones | Based on “training and experience” |

| Search Warrant | Applied weeks later | Relied on illegal search |

| Warrant Language | “Any and all items of evidentiary value” | Overbroad, unconstitutional |

The Automobile Exception: What Police Often Get Wrong

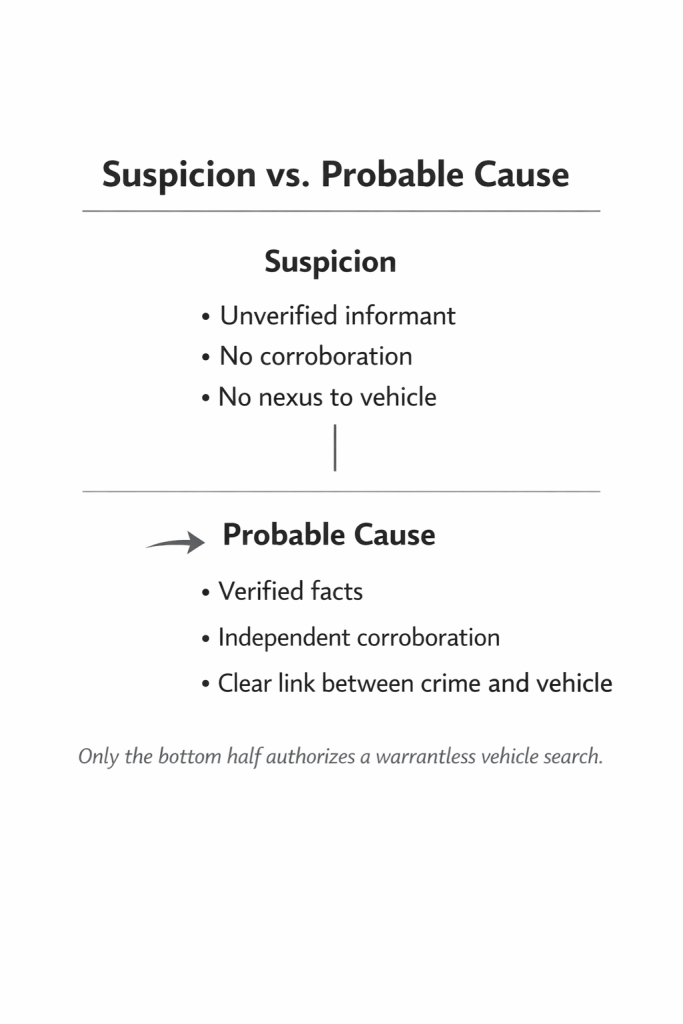

The automobile exception allows officers to search a vehicle without a warrant only when they have probable cause to believe evidence of a crime is inside the vehicle at that moment.

What Cabrera Leon teaches—forcefully—is this:

Suspicion, speculation, and possibility are not probable cause.

In this case, officers suspected the defendant might help a murder suspect flee. There was no evidence the car contained a weapon, blood, DNA, contraband, or anything tied to the homicide.

As the court bluntly observed, police acted on “nothing more than naked suspicion.”

Why the Stop Itself Didn’t Save the Search

Police attempted to justify the stop as a traffic infraction. The court dismantled that argument quickly.

Even if a traffic violation occurred, there is no search-incident-to-citation exception. A traffic stop does not authorize a full vehicle seizure or evidentiary fishing expedition.

As I often explain to clients:

“A lawful stop does not automatically justify an unlawful search.“

The Informant Problem: Why “Citizen Tips” Still Require Scrutiny

Law enforcement relied heavily on statements from the murder suspect’s estranged spouse. The court treated her exactly as defense lawyers argue such witnesses should be treated—with skepticism.

She was:

- Personally involved

- Emotionally motivated

- Unverified

- Uncorroborated

This mirrors long-standing Florida law: not every citizen is a “citizen informant.” Reliability still matters.

The Fatal Nexus Failure

Probable cause requires two elements:

- A crime occurred

- Evidence of that crime is likely in the place searched

The Cabrera Leon affidavit failed the second element completely.

There was no reason to believe:

- The murder weapon was in the car

- The victim’s DNA was in the car

- Any physical evidence of homicide was in the car

Without that nexus, the automobile exception collapses.

Why the Later Search Warrant Didn’t Cure the Violation

This is one of the most important lessons in the opinion.

Police often argue: “Even if the initial seizure was bad, we got a warrant later.”

That argument fails when:

- The warrant relies on illegally obtained observations

- The new information still lacks a nexus

- The warrant is overbroad

The court called this exactly what it was: fruit of the poisonous tree.

Overbroad Warrants and “Any and All Items of Evidentiary Value”

The warrant in Cabrera Leon authorized seizure of:

“Any and all items of evidentiary value.”

That phrase alone is enough to kill a warrant.

The Fourth Amendment does not permit general warrants. Officers cannot be allowed to decide for themselves what might be evidence.

As a trial lawyer, this language is something I look for immediately—it is often the weakest link in the prosecution’s case.

Cell Phone Searches: Double Constitutional Violations

The cell phones seized in this case were unknown to police until after the illegal stop. That fact alone doomed the phone warrants.

Even worse:

- No evidence showed the phones were used in the crime

- The alleged flight never happened

- The phones were seized based on “training and experience”

Modern courts recognize cell phones as digital containers of our lives. Without a clear nexus, warrants to search them fail.

Why the Good Faith Exception Didn’t Apply

Police attempted to rely on United States v. Leon. The court rejected that argument.

The good-faith exception does not apply when:

- The affidavit is facially deficient

- Probable cause is obviously lacking

- The warrant is clearly overbroad

An objectively reasonable officer should have known better.

How I Use This in Real Cases

When I litigate suppression motions, I can use this case to show:

- How automobile exception claims fail

- Why post-seizure warrants don’t sanitize violations

- Why cellphone searches require strict scrutiny

- How courts view overbroad warrant language

This is not academic law—it is trial-level, suppression-winning authority.

👉 If police searched your vehicle or phone, don’t assume it was legal.

https://www.centrallaw.com/contact-us/

Frequently Asked Questions

Police may only seize a vehicle without a warrant if they have probable cause to believe it contains evidence of a crime. Mere suspicion or unverified tips are not enough. Cabrera Leon makes clear that officers must articulate a specific evidentiary nexus.

No. A traffic stop alone does not authorize a search or seizure of your vehicle. There is no “search incident to citation” exception under Florida or federal law.

No. Courts reject the idea that phones are automatically evidence simply because crimes often involve communication. There must be probable cause tying the phone to the specific crime.

A later warrant does not fix an illegal seizure if it relies on information obtained unlawfully. Evidence gathered after an illegal stop may still be suppressed.

Warrants that authorize seizure of “any and all evidence” or leave discretion to officers violate the Fourth Amendment. Particularity is mandatory.

No. If the affidavit is obviously insufficient, the good faith exception does not apply. Cabrera Leon is a textbook example.

Yes. Especially when they are well-reasoned and cite controlling appellate authority. Judges read and respect opinions like this.

Only if it is reliable and corroborated. Emotionally involved or biased informants require verification.

The “fellow officer rule” does not excuse lack of probable cause. The requesting agency must have lawful grounds.

Absolutely. Many serious felony cases collapse once illegal evidence is suppressed.

Final Thought

The Fourth Amendment is not a technicality. It is a constitutional boundary. Cabrera Leon is a reminder that courts still enforce it—and that skilled defense litigation matters.

If your case involves a vehicle search, phone seizure, or warrant issue, this is the kind of analysis I bring to court.

👉 Speak with me directly about your case:

https://www.centrallaw.com/contact-us/

Full Text of the Cell Phone Search Opinion

33 Fla. L. Weekly Supp. 370a Online Reference: FLWSUPP 3309LEON

STATE OF FLORIDA, Plaintiff, v. MANUEL CABRERA LEON, Defendant. Circuit Court, 11th Judicial Circuit in and for Miami-Dade County, Criminal Division. Case No. F23-6326B. November 19, 2025. Milton Hirsch, Judge.

ORDER ON MOTION TO SUPPRESS

Defendant Manuel Cabrera Leon was stopped by deputies of the Hendry County Sheriff’s Office. The car in which he was driving was searched, and the car and its contents seized. Mr. Cabrera Leon moves to suppress the fruits of that search. A hearing was had on his motion on October 9. Transcript references herein are to that hearing. I. The stop, search, and seizure of the car Everton Morgan is a deputy in the Hendry County Sheriff’s Office. Tr. 8. On March 25, 2023, he was contacted by the Miami-Dade Sheriff’s Office. That office was investigating a homicide, and suspected that Cabrera Leon was somehow involved. Tr. 7, 9. The Miami-Dade officers were able to provide Deputy Morgan with a description of a car they believed belonged to Mr. Cabrera Leon, and with the location of a particular barbershop at which Cabrera Leon worked. Tr. 11. Armed with that information, Morgan and police colleagues went to the area of the barbershop. Tr. 12. When, quite late at night, Cabrera Leon left his place of work and drove off, the officers followed. Tr. 19. It was the testimony of Deputy Morgan that although the hour was late and the night dark, Mr. Cabrera Leon had his car’s lights turned off. Id. Shortly thereafter, the police officers pulled Cabrera Leon over. Tr. 20. There was much pointless fencing between defense counsel and Deputy Morgan about whether Mr. Cabrera Leon actually committed a traffic infraction (i.e., failure to have his lights on, see Fla. Stat. § 316.217) or not; and if so, whether the traffic infraction was the reason Cabrera Leon was pulled over. See, e.g., Tr. 24. Of course nothing could matter less. As I discuss infra, if the police had probable cause to believe that Mr. Cabrera Leon was involved in a homicide and that evidence of the homicide was to be found in the car, they were almost certainly empowered to stop and search the car pursuant to the “automobile exception” or “Carroll exception”1 to the Fourth Amendment warrant requirement. There was no need for Deputy Morgan to pretend that he and other detectives were genuinely interested in giving Cabrera Leon a ticket for a traffic infraction. Cf. Tr. 32 (prosecution stipulates that, “every stage where [the Hendry County Sheriff’s Office] participated in this stop and investigation was solely for the purpose of supporting the Miami investigation”). In truth if they had actually stopped Mr. Cabrera Leon to issue a traffic ticket — something that Deputy Morgan and I both know wasn’t the case — they could have done no more than ticket him and send him on his way. There is no “search incident to a valid traffic ticket” exception to the warrant requirement. Knowles v. Iowa, 525 U.S. 113 (1998). The car itself and its contents were seized.2 The reason for the seizure was not disputed. “[T]he purpose of having his car towed was to hand it over to Miami Homicide.” Tr. 28. A number of cellular phones found within the car were also taken by the police, in the hope — and nothing more than the hope — that they might prove to be of evidentiary value. Tr. 29. In Deputy Morgan’s words, the phones were seized because, “Based on my training and experience with a homicide typical[ly] communication is used, in today’s society, on a cell phone, a mobile device.” Tr. 35. With all due respect to Deputy Morgan’s training and experience, that is not a description of probable cause. The only witness to testify at the hearing other than Deputy Morgan was Pedro Camacho, a homicide sergeant in the Miami-Dade Sheriff’s Office. Tr. 47. On the evening of March 24, 2023, he and his colleagues in the Homicide Bureau learned of a shooting death in Hialeah Gardens. Tr. 48. Early on in their investigation they were contacted by a Yamila Rodriguez, who led them to believe that the murder was perpetrated by her estranged husband, Roberto Aveille Rodriguez. Tr. 50. According to Yamila, Roberto was planning to flee the country. Id. Again according to Yamila, Roberto would be aided in his efforts to escape by a friend with whom he had gotten as far as Collier County. Tr. 51. Having somehow identified the car that this friend would be driving, the Miami Homicide detectives contacted the Hendry County Sheriff’s Office, instructing deputies there “[t]o seize the vehicle and immediately contact us.” Tr. 52, 55. As described supra, the car and its contents were seized and, in due course, transported to Miami, where the car was held at a police storage facility. Some two-and-a-half weeks later, on April 11, Homicide Bureau detectives sought a search warrant for the car and its contents. Although Sgt. Camacho was not the affiant on the warrant application, the narrative of that document comports with the testimony that Camacho gave at the hearing on the motion to suppress. See gen’ly Tr. 48 et. seq. According to the affidavit, Yamila Rodriguez notified the police that Roberto Rodriguez had telephoned her, informing her that he had committed the murder in Hialeah Gardens and was planning to flee. Someone whom Yamila identified only as “Manolito” would help Roberto in his flight from justice. Somehow — the affidavit doesn’t say how — the police determined that “Manolito” was Manuel Cabrera Leon. They were able to identify his car and, by use of license-plate readers,3 to determine that his car was in Collier County. They instructed the Hendry County officers to stop and seize the car, and those officers did so. Although the car and its contents were impounded, Mr. Cabrera Leon was released. The Miami-Dade police officers gathered additional information to support their warrant application in the days after the seizure of the car, but the foregoing is the information of which they were possessed when they instructed their colleagues in Hendry County to stop Mr. Cabrera Leon and seize his car. In summary, then: police, bedecked with the accouterments of office but without a thread of judicial authority, acting on uncorroborated gossip, stopped a man along the side of a public roadway in the dark of night, took from him his car and all its contents, and left him to fend for himself. Such police conduct has been described by at least one Florida court as, “evok[ing] images of other days, under other flags, when no man traveled his nation’s roads or railways without fear of unwarranted interruption, by individuals who held temporary power in the Government. The spectre of American citizens being asked,” — or in this case, forced — “by badge-wielding police, [to produce] identification, [and] travel papers [and to surrender their car and personal property]. . . is foreign to any fair reading of the Constitution, and its guarantee of human liberties.” State v. Kerwick, 512 So. 2d 347, 348 (Fla. 4th DCA 1987) (emphasis in original). By their actions, warrantless and unwarranted, the police deprived a man of his car, of his means of transportation, of his valuable personal property; but it is not the mere deprivation of property, “[i]t is not the breaking of his doors, and the rummaging of his drawers, that constitutes the essence of the offence [against the Constitution]; . . . it is the invasion of his indefeasible right of personal security [and] personal liberty . . . , it is the invasion of this sacred right which underlies and constitutes the essence of” the violation of the Fourth Amendment. Boyd v. United States, 116 U.S. 616, 630 (1886).4 The Supreme Court has “had frequent occasion to point out that a search is not to be made legal by what it turns up. In law it is good or bad when it starts and does not change character from its success.” United States v. DiRe, 332 U.S. 581, 595 (1948) (Jackson, J.) (citing Byars v. United States, 273 U.S. 28 (1927)). See also Jones v. Securities & Exchange Commission, 298 U.S. 1, 27 (1936) (a search that “is unlawful at its inception . . . cannot be made lawful by what it may bring, or by what it actually succeeds in bringing, to light”). If at the time police stopped, searched, and seized Miguel Cabrera Leon’s car they had legal justification to do so, then the fruits of their search and seizure, including their observations in connection with that search and seizure, are admissible in court. In addition, those fruits, including those observations, when coupled with after-acquired information, could lawfully support the police applications for warrants later obtained. If, on the other hand, the initial stop, search, and seizure of Cabrera Leon’s car was without legal justification, then the fruits of that search and seizure cannot be used for any purpose. The Fourth Amendment provides: The right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated, and no Warrants shall issue, but upon probable cause, supported by Oath or affirmation, and particularly describing the place to be searched, and the persons or things to be seized. From the foregoing language, a general principle has been culled which is at this date too well-settled to invite citation to authority: that searches conducted pursuant to warrant are presumed to be reasonable for Fourth Amendment purposes,5 but that the reasonableness of searches conducted in the absence of warrant must be established. As noted supra at 2, one of the well-established exceptions to the warrant requirement is sometimes termed the “automobile exception.” Carroll v. United States, 267 U.S. 132 (1925) was a Prohibition-era case. Federal agents stopped a car that they had reason to believe was transporting liquor illegally imported from Canada. Applicable federal statutory law clearly manifested “[t]he intent of Congress to make a distinction between the necessity for a search warrant in the searching of private dwellings and in that of automobiles and other road vehicles in the enforcement of the Prohibition Act.” Carroll, 267 U.S. 147. The Court stated a broad general rule: [T]he Fourth Amendment has been construed, practically since the beginning of the Government, as recognizing a necessary difference between a search of a store, dwelling house or other structure in respect of which a proper official warrant readily may be obtained, and a search of a ship, motor boat, wagon or automobile, for contraband goods, where it is not practicable to secure a warrant because the vehicle can be quickly moved out of the locality or jurisdiction in which the warrant must be sought. Id. at 153. Whether the facts and law justified so broad a rule as the Carroll court pronounced is a nice question. The federal agents in Carroll acted pursuant to probable cause, but also pursuant to legislative authority. And that being the case, “the Carroll decision falls short of establishing a doctrine that, without such legislation, automobiles nonetheless are subject to search without warrant.” United States v. DiRe, 332 U.S. at 585. That, however, is how Carroll has consistently been understood, in Florida and elsewhere. See, e.g., Jones v. State, 325 So. 3d 101, 102 (Fla. 5th DCA 2020) [45 Fla. L. Weekly D201b] (“Pursuant to the automobile exception, law enforcement may conduct a warrantless search of a vehicle based upon probable cause to believe that the vehicle contains evidence of criminal activity”) (citing Carroll). At the time the Hendry County deputy sheriffs, acting at the instruction of the Miami-Dade Homicide Bureau detectives, stopped, seized, and searched Mr. Cabrera Leon’s car, they had no warrant. Did they have probable cause to believe that the car contained evidence of crime?6 So far as appears, at the time the Miami-Dade officers contacted their Hendry counterparts, they knew that a homicide had been committed. Early on in their investigation, “it was learned that Yamila Rodriguez . . . had contacted law enforcement because she had information about the” homicide. Affidavit for Search Warrant p. 5. The affiant’s use of the passive voice leaves questions unanswered. How did the police come in contact with Yamila? Did they bother to learn anything about her? Is she a model citizen or an oft-convicted felon? Apparently she claims that her estranged husband telephoned her to confess to the murder under investigation. Id. Is there any way to corroborate this conversation, as for example by phone records; or is it the uncorroborated and perhaps vengeful tattle-taling of a woman scorned — like whom Hell, William Congreve tells us, hath no fury?7 A so-called “citizen informant” — one who provides information not for money, nor in order to go unwhipped of justice, but out of a sense of civic duty — is the darling of the law. See, e.g., State v. Maynard, 783 So. 2d 226 (Fla. 2001) [26 Fla. L. Weekly S182b]; State v. Manuel, 796 So. 2d 602 (Fla. 4th DCA 2001) [26 Fla. L. Weekly D2214b]; State v. Ramos, 755 So. 2d 836 (Fla. 5th DCA 2000) [25 Fla. L. Weekly D1108a]; Grant v. State, 718 So. 2d 238, 239-40 (Fla. 2d DCA 1998) [23 Fla. L. Weekly D1969a]. But not everyone possessed of citizenship qualifies as a “citizen informant,” as to whom reliability is presumed. The informant in Dial v. State, 798 So. 2d 880 (Fla. 4th DCA 2001) [26 Fla. L. Weekly D2645a] was the 13-year-old daughter or stepdaughter of the defendant. She presented herself at the local police station alleging that she had been abused, although the police officers saw no signs of physical abuse and no abuse charges had ever been filed. Dial v. State, 798 So. 2d at 881. She then alleged that Dial was counterfeiting money. Id. In the course of her narrative she acknowledged that Dial had recently scolded and grounded her for misbehavior at school. Id. The warrant affidavit subsequently presented to a judge made no mention of the familial relationship between Dial and the “citizen informant,” nor of the strain that had been placed on that relationship by Dial’s attempt to discipline the child. Id. at 882. Although the police obtained a warrant, and their search did turn up counterfeit currency, the court of appeal reversed the trial court’s denial of the defendant’s motion to suppress. The daughter had never before been used by the . . . [police] as a confidential informant . . . . She had not previously furnished reliable information to the . . . police. [The police] had no other information concerning illegal activity at [Dial’s] home. The officers did not run a juvenile records check on the girl or take any steps to ascertain the owner of the property or confirm that she and [Dial] actually lived there. Id. Thus the facts “did not indicate that the informant was simply an honest, disinterested citizen reporting a crime and lacking a motive to make false allegations against the suspect. The informant . . . did not qualify as a citizen informant. . . . [H]er reliability needed to be verified or corroborated by facts contained in the affidavit. Here, the affidavit failed to furnish such facts and was thus deficient.” Id. at 883 (internal quotation marks omitted). Surely the same is true of Yamila. The police knew nothing about her. She had never before provided information to the police. She was, by her own admission, something much less than disinterested. But there was no verification or corroboration of her or of her story, none at all, at least so far as appears in the warrant affidavit or Sgt. Camacho’s testimony. Yamila, according to the affidavit, “further stated that a male who [sic; whom] she identified as ‘Manolito,’ was going to transport [Yamila’s estranged husband, the murder suspect] to an unknown location. Detectives identified ‘Manolito’ as Manuel Cabrera Leon . . . who owns” a particular car. Affidavit for Search Warrant p. 5. How did Yamila know Manolito? How did she know that he was planning to drive her estranged husband to “an unknown location”? Of all the unnumbered men in South Florida who sometimes use the nickname “Manolito,” how is it that the detectives identified this Manolito as Manuel Cabrera Leon? Neither the affidavit, nor Sgt. Camacho’s testimony at the hearing, supplies answers to these questions. Perhaps most importantly: Probable cause requires reason to believe that a crime has been committed and that evidence of that crime is to be found in the place to be searched or thing to be seized. What evidence of homicide was to be found in Mr. Cabrera Leon’s car? What reason did the police have to believe it would be found there? When the car was stopped and searched, cellphones were found; but the police knew nothing of those phones before the car was stopped and searched. Although the car and the phones were impounded, Cabrera Leon was released; and as for Roberto Aveille Rodriguez, he was nowhere to be seen. Again, what evidence of homicide (or any other felony) did the police reasonably believe was to be found in the car? The police had no intelligence that, for example, the murder weapon was to be found in the car; nor the blood or other genetic or biological material of the murder victim; nor any distinctive property associated with the victim. Such evidentiary artifacts, if there was a reasonable basis to believe they could be found in Mr. Cabrera Leon’s car, would have provided probable cause for the stop and search of the car. But so far as the affidavit relates, and so far as Sgt. Camacho’s testimony goes, the police had no reason to believe that any such evidence was in the car. If the narrative of this case ended with the seizure of the car allegedly driven by Mr. Cabrera Leon, this would be an easy case. At the time of the stop and seizure the police had nothing more than naked suspicion that fruits, instrumentalities, or evidence, of any crime, much less of the crime under investigation, were to be found in the car. Deputy Morgan all but admitted as much: “I was on the phone with Miami-Dade during the traffic stop and the information that I receive is this vehicle possibly had some evidence, that it could be possible to have evidence pending [sic; tending?] toward aiding in the homicide” investigation. Tr. 33 (emphasis added). II. The warrant for the search of the car But the narrative of this case does not end with the seizure of the car. The car was brought to Miami and held in police custody. Several weeks later, on April 12, 2023, the police sought and obtained a warrant for the search of the car. The warrant application includes the information that was known to the police at the time the Hendry County officers stopped and seized the car — information insufficient to justify that stop and seizure — as well as information learned after the fact. It includes, for example, information that Roberto Aveille Rodriguez had, on March 26, provided a plenary confession to the murder; and information regarding follow-up investigation that offered some corroboration of that confession. That said, the warrant was certainly inadequate. To begin with, it relied chiefly on the observations made by officers as a consequence of the constitutionally-offensive stop and search of Mr. Cabrera Leon’s car. Those observations were fruit of the poisonous tree, and they could not be rendered nutritious and delicious by marinating them in a warrant and topping them with a judicial signature. After-acquired information helped support the warrant, but it didn’t help enough. Mr. Aveille Rodriguez’s confession, so far as appears from the warrant affidavit, did not suggest that evidence of his crime was to be found in Cabrera Leon’s car. The police obtained a store video from Walmart that appeared to show Mr. Cabrera Leon purchasing cell phones, perhaps the cell phones found in his car. But it is not a crime, nor evidence of a crime, to purchase, possess, or transport cell phones. When we say that a search warrant must be supported by probable cause, To establish the requisite probable cause for the search warrant, the affidavit submitted in support of the warrant must set forth facts establishing two elements: (1) the commission element — that a particular person has committed a crime; and (2) the nexus element — that evidence relevant to the probable criminality is likely to be located in the place searched. State v. Hart, 308 So. 3d 232, 235 (Fla. 5th DCA 2020) [45 Fla. L. Weekly D2607d] (citing State v. McGill, 125 So. 3d 343, 348 (Fla. 5th DCA 2013) [38 Fla. L. Weekly D2340b]). See also State v. Acevedo, 366 So. 3d 1096, 1101 (Fla. 4th DCA 2023) [48 Fla. L. Weekly D1138a] (“To issue a search warrant, the issuing judge must find proof of two elements: (1) the commission element, that a particular person committed a crime; and (2) the nexus element, that relevant evidence of probable criminality is likely to be found in the place searched”); Burnett v. State, 848 So. 2d 1170, 1173 (Fla. 2d DCA 2003) [28 Fla. L. Weekly D1179b] (“[T]he affidavit in the warrant application must satisfy two elements: first, that a particular person has committed a crime — the commission element, and, second, that evidence relevant to the probable criminality is likely located at the place to be searched — the nexus element”). Here, the nexus element fails. There is nothing in the warrant application that supports a reasonable belief that evidence of the demised homicide is to be found in the car — particularly because the cellphones had already been removed from the car. Apart from the requirement of probable cause, there is the requirement of particularity. A valid warrant must “particularly describ[e] . . . the things to be seized.” U.S. Const. Amend. IV. The purpose of the particularity requirement is to “stand[ ] as a bar to exploratory searches by officers armed with a general warrant . . . [and to] limit[ ] the searching officer’s discretion in the execution of a search warrant, thus safeguarding the privacy and security of individuals against arbitrary invasions of governmental officials.” Carlton v. State, 449 So. 2d 250, 252 (Fla. 1984). The requirement of particularity is not met if the warrant purports to vest the officers executing it with discretion to determine what to search or what to seize. On the contrary: American courts have long been adamant that, “As to what is to be taken, nothing is left to the discretion of the officer executing the warrant.” Marron v. United States, 275 U.S. 192, 196 (1927). Compliance with the particularity requirement, “is accomplished by removing from the officer executing the warrant all discretion as to what is to be seized.” United States v. Torch, 609 F. 2d 1088, 1089 (4th Cir. 1979). See also Pezzella v. State, 390 So. 2d 97, 99 (Fla. 3d DCA 1980) (“if a warrant fails to adequately specify the material to be seized, thereby leaving the scope of the seizure to the discretion of the executing officer, it is constitutionally overbroad”). The warrant at bar purports to authorize the officers to search the car for any and all forms of firearms and weapons. (What evidence was there of a firearm or weapon in the car?) It authorizes a search for “clothing, wallets, documents, receipts,” and for “computer equipment,” (again, what evidence was there of such things in the car?) and — crowning it all — for “Any and all items of evidentiary value.” If a warrant can authorize the search of any and all items which strike the searching officers as perhaps possessing “evidentiary value,” the particularity requirement is read out of the Fourth Amendment, and the Fourth Amendment out of the Constitution. I recognize that I owe a duty of deference to the on-duty judge who signed the warrant for the search of the car. State v. Carreno, 35 So. 3d 125, 128-29 (Fla. 3d DCA 2010) [35 Fla. L. Weekly D1125a]. See also State v. Oliveras, 65 So. 3d 1162, 1165 (Fla. 5th DCA 2011) [36 Fla. L. Weekly D1573a] (“When reviewing a prior determination of probable cause and the issuance of a search warrant, the reviewing circuit judge must accord deference to the issuing judge’s determination, presume it to be correct, and not disturb that determination unless there is clear showing that the issuing judge abused his or her discretion”); State v. Abbey, 28 So. 3d 208, 210 (Fla. 4th DCA 2010) [35 Fla. L. Weekly D471a]. See gen’ly Willacy v. State, 967 So. 2d 131, 147 (Fla. 2007) [32 Fla. L. Weekly S377a]. That said, I note in passing that there is something incongruous about this duty of deference. Ours is the adversary system of justice. It is premised on the notion that due process will likely be provided, and the truth will likely come to light, when each side is afforded the opportunity to present its own evidence and to probe the opponent’s evidence. It must follow that due process is less likely to be provided, and the truth is less likely to come to light, in ex parte, non-evidentiary proceedings. The work of a warrant-duty judge is, with very rare exceptions, nothing but a series of ex parte, non-evidentiary proceedings. That judge is presented with an affidavit. That judge takes no testimony. There is neither direct nor cross-examination. There is no opportunity to consider the demeanor, the facial expressions, the tone of voice of the affiant. There is no chance for the target of the warrant to be heard. By contrast, a hearing on a pretrial motion to suppress, such as I conducted in this case, is an adversary proceeding. A judge takes testimony, subject to direct and cross-examination. The judge carefully observes the demeanor of each witness. Both sides pose questions and make argument. Yet the law provides that the judge who has had the benefit of an adversarial, evidentiary proceeding as I did in this case; the judge who has observed the witnesses and drawn his own conclusions about their credibility as I did in this case; the judge who has had the benefit of hearing from both sides as I did in this case; must afford deference to the decision made by the judge who was awakened to sign an ex parte submission in his or her pyjamas. However incongruous this rule of law, it is a rule of law. I owe a duty of deference to the decision made by my colleague who signed the warrant. That said, I owe a greater duty of deference to the Constitution. The police, with show of force, stopped Mr. Cabrera and searched his car; seized the car and its contents; and after some bullyragging,8 told Cabrera to be on his way. These things they did without a warrant, and without anything resembling probable cause. Their observations thus unconstitutionally obtained formed much of the basis of their warrant application. Those observations were supplemented by additional investigative work that did unearth new information, but not information that pointed to Mr. Cabrera Leon’s car as being a repository of physical evidence of the homicide under investigation. A warrant, thus based on evidence that was either unconstitutionally procured or lacking in probative value, was issued in derogation of the probable cause and particularity requirements of the Fourth Amendment. (Even ignoring all the warrant’s other shortcomings, the purported authorization to search for and seize “any and all items of evidentiary value” renders the warrant fatally overbroad.) I cannot close my eyes to these constitutional infirmities in the name of collegial deference, or in the name of anything else. I recognize, too, that the fruits of an invalid warrant may nonetheless be admissible pursuant to the so-called “good faith exception” to the Fourth Amendment exclusionary principle. The “good-faith exception” has its genesis in United States v. Leon, 468 U.S. 897 (1984), and proceeds from the Leon Court’s premise that, “when law enforcement officers have acted in objective good faith [in obtaining and relying on a warrant] . . . the magnitude of the benefit conferred on . . . guilty defendants [by operation of the exclusionary rule] offends basic concepts of the criminal justice system.” Leon, 468 U.S. at 908. When police officers present a warrant application to an on-duty judge, obtain a warrant based on that application from that judge, and then act on that warrant to search or seize, the officers — so the “good-faith exception” teaches — have done all that is required of them. An after-the-fact determination that the warrant was defective should not invalidate the search based upon it, or render inadmissible the fruits of that search; permitting those fruits to be received in evidence at trial provides police with an incentive to seek warrants rather than to proceed in their absence. And that — again, so the “good-faith exception” teaches — is what the exclusionary rule, and the Fourth Amendment itself, are intended to achieve. Id., passim, esp. at 913-14.9 Whatever the merits or demerits of Leon’s good-faith doctrine, it is the law. But so, too, is an exception to that doctrine. For the good-faith exception to be applicable, the police must have “acted in an objectively reasonable manner, in objective good faith, and as a reasonably well-trained officer would act.” Pilieci v. State, 991 So. 2d 883, 896 (Fla. 2d DCA 2008) [33 Fla. L. Weekly D966b] (Altenbernd, J.). The exception cannot be applied in “circumstances in which an objectively reasonable officer would have known the affidavit . . . w[as] insufficient to establish probable cause for the search.” Pilieci, 991 So. 2d at 896. See also Garcia v. State, 872 So. 2d 326, 330 (Fla. 2d DCA 2004) [29 Fla. L. Weekly D892b]. Those circumstances are present here. As detailed hereinabove, the warrant was based upon facts obtained in gross violation of the Fourth Amendment, and was cast in language not conforming to the probable-cause and particularity requirements of that Amendment. The test is an objective one. A reasonable police officer, possessed of that training and discretion required of police officers, is obliged to know better than to act upon such a warrant. Of course all this may be much ado about nothing. Recall that when the Hendry County officers stopped and searched Mr. Cabrera Leon’s car on that dark stretch of road, the only items that struck them as perhaps being of evidentiary value were half-a-dozen cellphones. They removed the phones from the car and provided them to the Miami-Dade Homicide Bureau. As to those phones, the Miami-Dade officers then sought a warrant, separate and apart from the warrant for the search of the car. Whether there was anything found in the car, other than the phones, that the prosecution will want to use in evidence at trial was never made entirely clear at the hearing on the motion to suppress.10 III. The warrant for the search of the cellphones The warrant application identifies six cellular phones removed from Mr. Cabrera Leon’s car, and seeks authorization to conduct a forensic examination of their contents. Generally, the factual recitation in the application is the same as appears in the application for the warrant to search the car. Apropos the phones themselves, the affidavit relates that Cabrera Leon purchased four Nokia TracFones, keeping one for himself, giving one to Aveille Rodriguez, giving another to a Yanier Hernandez, and intending at some point in the future to give one to Aveille Rodriguez’s girlfriend (not — decidedly not — Yamila Rodriguez). The police obtained video from a local Walmart showing Mr. Cabrera Leon purchasing four phones.11 Aveille Rodriguez confessed to the murder for which he was sought; in that confession he alleged that he told Cabrera Leon what he had done, and alleged that he stayed for an unspecified period of time at Cabrera Leon’s home. So far as appears, Mr. Aveille Rodriguez had these conversations with Mr. Cabrera Leon in person, not via cellphone. The warrant application suggests that the phones were to be used by Aveille Rodriguez’s friends, including Cabrera Leon, to stay in touch with him after he fled the country. But he did not flee the country — he stayed, and confessed his crime to the police. Is there any reason to believe that the phones were ever used? Is there any reason to believe that they were used in such a manner as to contain evidence of the homicide under investigation? No such reasons are offered in the warrant application. But apart from that, this warrant for the forensic search of the phones founders on the same rocks as did the warrant for the search of the car. At the time that the police, acting on nothing more than unalloyed suspicion, stopped, seized, and searched Mr. Cabrera Leon’s car, they were blithely unaware of the existence of these cellphones. When they saw the phones in the car they seized them. (Recall that the basis for the seizure was Deputy Morgan’s belief that “with a homicide typical[ly] communication is used, in today’s society, on a cell phone,” see supra at 3.) True, between the time of that unconstitutional seizure and the police application for a warrant to examine the phones, the police had the benefit of Mr. Aveille Rodriguez’s confession. But so far as appears in the warrant application, Aveille Rodriguez was never asked if he and his friends had used those phones to perpetrate or cover up the murder he committed; and he never volunteered any information on that score. There was no independent investigation that ineluctably led, or would have led, to the cellphones.12 The infirmities that afflict the warrant for the search of the car afflict the warrant for the search of the cellphones. It is unnecessary to repeat the analysis and the authorities that detail those infirmities. As to Mr. Cabrera Leon, the phones and their content are inadmissible. IV. Conclusion As noted supra, this may be much ado about nothing. At the hearing on the motion to suppress, nothing of great probative value was identified as being among the fruits of the various searches here. Granting or denying suppression may have little or no effect on the outcome of this litigation. The police already have that most powerful of weapons in the prosecutorial arsenal, the confession of a murderer. But that is not the point. In 1949, Justice Robert Jackson had recently returned to the Court from his duties as chief prosecutor at the Nuremberg war crimes trials. He had traveled extensively in post-war Germany. He had seen the sequelae of Naziism and war, and he had learned from what he had seen. In his dissenting opinion in Brinegar v. United States, 338 U.S. 160, 180-81 (1949), he shared what he had learned with the American people: When this Court recently has promulgated a philosophy that some rights derived from the Constitution are entitled to “a preferred position,” . . . I have not agreed. We cannot give some constitutional rights a preferred position without relegating others to a deferred position; we can establish no firsts without thereby establishing seconds. Indications are not wanting that Fourth Amendment freedoms are tacitly marked as secondary rights, to be relegated to a deferred position. . . . These, I protest, are not mere second-class rights but belong in the catalog of indispensable freedoms. Among deprivations of rights, none is so effective in cowing a population, crushing the spirit of the individual and putting terror in every heart. Uncontrolled search and seizure is one of the first and most effective weapons in the arsenal of every arbitrary government. And one need only briefly to have dwelt and worked among a people possessed of many admirable qualities but deprived of these rights to know that the human personality deteriorates and dignity and self-reliance disappear where homes, persons and possessions are subject at any hour to unheralded search and seizure by the police. But the right to be secure against searches and seizures is one of the most difficult to protect. Since the officers are themselves the chief invaders, there is no enforcement outside of court. Enforcement of this indispensable constitutional right to be free from unreasonable search and seizure — enforcement of the simple command that the privacy and sanctity of the home, the integrity and autonomy of the self, “shall not be violated,” U.S. Const., Amend. IV — is consigned to the courts, and to the lawyers who come before those courts. Justice Jackson states no more than the obvious when he acknowledges that, because law enforcement officers are themselves the chief invaders of those rights, there can be no enforcement elsewhere than in the courts. Enforcement comes by application of the Fourth Amendment’s exclusionary principle. That principle, see supra n. 9, is readily and regularly castigated. See, e.g., Davis v. United States, 564 U.S. 229, 237 (2011) [22 Fla. L. Weekly Fed. S1144a] (a “bitter pill,” a “last resort”). In a case entirely unrelated to this one, a very fine young prosecutor, in argument before me, referred to “the cold and unforgiving hand” of the exclusionary rule. As discussed supra at 16 et. seq. in connection with the Leon doctrine, the hand of the exclusionary rule is far from unforgiving. But if the hand of the exclusionary rule is cold, it has grown cold — and worn, and tired too — ceaselessly sheltering the homes, the hearths, and the freedoms of Americans. Better that cold and unforgiving hand than the mailed fist of tyranny. Defendant’s motion to suppress is respectfully GRANTED. ______ 1See Carroll v. United States, 267 U.S. 132 (1925). See also Chambers v. Maroney, 399 U.S. 42 (1970). See discussion infra at 7 et. seq. 2I find that Mr. Cabrera Leon did not consent to the search of his car or the seizure of his property. I mention this only because the warrants — written by Miami-Dade officers who were at the opposite side of the state when the search and seizure was conducted — allege that he did consent. Deputy Morgan, who had an very imperfect recollection of the evening’s events, could say no more than that, “I really don’t recall, but I want to say that he possibly gave his consent or it was during the inventory.” Tr. 29. I believe Deputy Morgan when he says he really doesn’t recall. I don’t believe that Cabrera Leon gave a knowing and voluntary consent to anything. 3See gen’ly https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Automatic_number-plate_recognition. See Fla. Stat. § 316.0777. 4It is, of course, no answer to say that this sort of thing occurs from time to time in our present-day society, and that we ought by now to be inured to it. Facilis descensus averno. It is the duty of courts charged with upholding the rights of liberty and the usages of democracy to refuse to become inured to it. As Alexander Pope reminds us in his “Essay on Man:” Vice is a monster of so frightful mien As to be hated needs but to be seen; Yet see too oft, familiar with her face, We first endure, then pity, then embrace. 5Although the Florida Constitution has, at Art. I § 12, a guarantee against unreasonable search and seizure, that guarantee is rendered inert by a “conformity clause,” i.e., a provision that the right set forth in the Florida constitution must be interpreted no differently than the Fourth Amendment is interpreted by the United States Supreme Court. Because the Florida constitutional language does not afford us any protection as Floridians that we do not already enjoy as Americans, I refer in this order to the Fourth Amendment, and not to the Fourth Amendment and Art. I § 12. 6If the question is posed literally, the answer must be “no.” The Hendry County officers knew nothing more than that their Miami-Dade County colleagues had told them to stop and seize a car. They had no cause for that stop and seizure, probable or otherwise. Pursuant to the “fellow officer rule,” however, if facts constituting probable cause to seize and search were in the possession of the Miami-Dade officers, knowledge of those facts will be imputed to, and justify the conduct of, the Hendry officers. See Whiteley v. Warden, Wyoming State Penitentiary, 401 U.S. 560 (1971); Crawford v. State, 334 So. 2d 141 (Fla. 3d DCA 1976). 7The actual quote from Congreve’s The Mourning Bride is, “Heaven has no rage, like love to hatred turned, nor Hell a fury like a woman scorned.” 8Deputy Morgan admitted that he and his colleagues harangued Mr. Cabrera Leon for the whereabouts of Aveille Rodriguez, even threatening Cabrera Leon that he would go to jail if he didn’t tell them. Tr. 31. When that didn’t work, they abandoned him by the side of the road. 9Of course a very forcible argument could be made to the contrary. In Weeks v. United States, 232 U.S. 383 (1914), the Court had occasion for the first time to explain that although the common law had provided a right to be free from arbitrary search and seizure, it had provided no remedy for breach of that right. The Weeks Court further explained that the Fourth Amendment was enacted expressly to provide that remedy by excluding evidence unlawfully obtained. “The case . . . involves the right of the court in a criminal prosecution to retain for the purposes of evidence the [property] of the accused, seized . . . [without] warrant . . . for the search. . . . If [evidence] can thus be seized and held and used in evidence against a citizen accused of an offense, the protection of the Fourth Amendment . . . is of no value.” Weeks, 232 U.S. at 393 (emphasis added). See also Samuel Dash, The Intruders: Unreasonable Searches and Seizures from King John to John Ashcroft 62-63 (2004). What the Fourth Amendment purports to secure is not the right to be free from unreasonable searches and seizures conducted in bad faith, but the right to be free from unreasonable searches and seizures — period. And it secures that right by the exclusion of evidence, so that officers of the judicial branch do not repeat — indeed aggravate — the sins of the officers of the executive branch. The “benefits [of the Fourth Amendment] are illusory indeed if they are denied to persons who may have been convicted by the very means which the Amendment forbids.” Goldman v. United States, 316 U.S. 129, 142 (1942) (Murphy, J., dissenting) 10According to the motion at bar, the defense seeks to suppress, “Walmart receipts, several cellphones, cellphone boxes, phone activation cards, and any evidence derived therefrom.” 11Both the warrant application and the warrant refer to six phones. Three are identified as Nokias, two as Samsungs, and one as a Motorola. The probable-cause narrative in the application, however, refers to four Nokia phones. I do not know how this discrepancy is to be reconciled. Which phones were the police asking to search? Which phones was the warrant-duty judge authorizing the police to search? Can police reasonably rely on a warrant hobbled with this discrepancy? 12I mention this because at the hearing on the motion to suppress, the prosecution made reference to the “inevitable discovery” doctrine. Tr. 68. The inevitable discovery doctrine is applicable when a lawfully-conducted police investigation is in train, which investigation inevitably would have led by lawful means to the discovery of the same fruits actually obtained by lawless means. That the police could have gotten a warrant and retrieved evidence is not enough; they must be able to say that, at or before the time of the constitutionally-impermissible conduct, they would have gotten a warrant and obtained that evidence. See Shingles v. State, 872 So. 2d 434, 439 n. 3 (Fla. 4th DCA 2004) [29 Fla. L. Weekly D1149a]. See also Rowell v. State, 83 So. 3d 990, 996 (Fla. 4th DCA 2012) [37 Fla. L. Weekly D745a]: [C]ontrary to the state’s argument, the inevitable discovery doctrine does not apply merely because the police may have had probable cause to obtain a search warrant [at the time of the primary illegality]. In this case . . . the prosecution made absolutely no showing that efforts to obtain a warrant were being actively pursued prior to the occurrence of the illegal conduct. Operation of the “inevitable discovery” rule under the circumstances of this case would effectively nullify the requirement of a search warrant under the Fourth Amendment. (Emphasis added.) *